The author of the article is Arantza Diaz, frim México

Why can't women be priests?: A look at the forbidden and criminalized vocation

Mexico City.- Who measures faith, and how do they decide which faiths are more valuable than others? What happens to women who have miraculous awakenings and cannot be ordained as priests because they are women? This is the basis of the revolution of thousands of women around the world who have risen up to demand that the Vatican and its world of bureaucracy allow the advancement of women; no longer as caregivers and nuns, but as prophets with the power to lead the Church.

Overthrowing a 2,000-year-old system is impossible, especially in a structure as powerful as the Catholic Church, which, despite denying sexism within its ranks, cannot easily disassociate itself from patriarchy. There are no women making decisions; everything is achieved through male consensus; celibate men who will never have wives, much less daughters. It's difficult to fathom how far women's agendas can be hindered, not so much due to a lack of empathy, but rather due to a patriarchal gynophobia—as Evangelina García describes it—that infers an "inability to recognize the female experience."

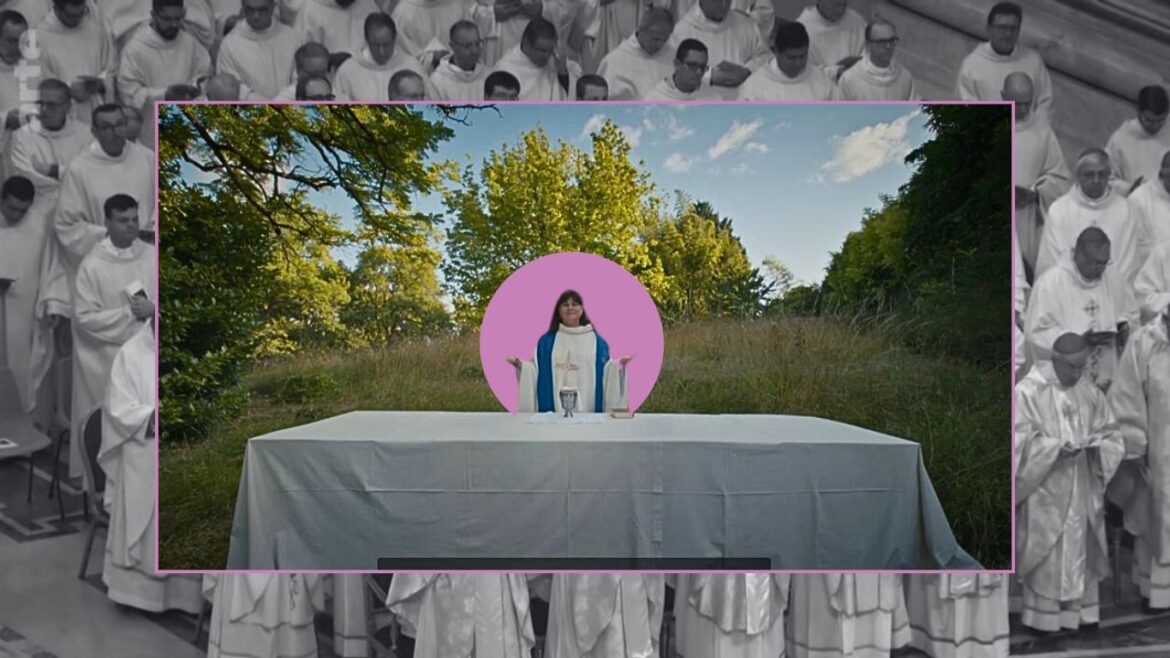

Marie Mandy's documentary "Women Priests" follows the stories of several women who have demanded that the Church ordain them as priests; many of them threatened and intimidated by the clerical force that has attempted to undermine their faith, claiming it is not powerful enough to be recognized as priests—not out of whim, but because it is a canonical law of the Church that has historically barred women from decision-making.

However, it is important to note that, despite being denied entry to these spaces, women are not denied their work as caregivers and primary protectors of the Church. Their work is extracted; it is women who care for the churches in their communities, who organize, clean, celebrate, and sustain the Catholic faith.

The 7 Danube

On Palm Sunday 2002, seven women were ordained deaconesses by the Catholic Church. One of them, Christine Mayr Lumetzberger, recalls the fear they felt during the ceremony.

This group of women, who had dedicated their entire lives to the Church and contributed to community service for decades, were now receiving death threats for their intentions to be ordained; they were warned that bombs would be planted in their church or even a shooting would be started to prevent the ceremony.

As a result, the seven Catholics decided to have their ordination on a boat; a private event attended by a Vatican representative who named them deaconesses. The event proved historic and, for Mayr Lumetzberger, marked the highest point of her life; her main purpose in life was to serve God, and with the appointment, her aspirations had been fulfilled.

Since they were seven women, they earned the nickname "The Danube Seven"—because of the way they were ordained on water—but they didn't expect a setback from the Catholic Church itself.

"They were furious, and it was intimidating," Mayr Lumetzberger recalls. Their persecution began, and they denounced each other for being made out to be a "true coven of witches," as if their appointment had been a complete violation of God's will; an unforgivable act that would condemn them forever.

At that time, John Paul II spoke out in a visibly dissatisfied manner, denouncing that the appointment of the Danube 7 would never have the authorization of the Lord and after 6 weeks of intimidating public acts, this group of nuns was excommunicated by the Church: "They decided to punish us," says Gisela Forster, who belongs to the Danube group.

However, the struggle did not end there, and after a hard fight against the Church, only two of them managed to return to ecclesiastical work. Mayr Lumetzberger and her counterpart, Gisela Forster, were appointed bishops. This, of course, upset many members of the Church, and to this day, they continue to reject the appointment, making it clear that their faith and their work are invalid.

Despite the collective rejection of the Catholic bureaucracy, and with power in their hands, Gisela and Mayr initiated a complete revolution by ordaining more women. It was through their experience that they were able to expand their faith; they listened to the experiences of many more women who claimed to have miraculous revelations and their helplessness in serving the Lord.

As a result, both bishops have managed to ordain:

- 9 women in the St. Lawrence River in Canada

- 8 women in the Ohio River, Pittsburgh, United States

- 1 woman named Genevieve Beney in Lyon, France

- The first African-American woman named Myra Brown in New York, who was recognized as a deaconess in 2015 and two years later, was elevated to priestess

Myra Brown has been a key player in New York's social movements, calling on her Church to actively participate in the Black Lives Matter movement . The now-priestess recalls that she dedicated her entire life to the Church and always heard the priest speak of "The Man," as if it were synonymous with humanity. However, when she looked around, "85% of the people there were women. Women kept the church going," says Myra Brown.

Deriving from this, the priestess came to the greatest revelation:

"Women should keep quiet"

The documentary follows the story of Jacqueline Straub, a journalist and theologian who, since the age of 14, claims to have been sought by the Lord. This process is known as "the calling," however, according to the Church, this feeling can only be experienced by men; men whom the Lord seeks with the important mission of spreading his work and word.

However, in a world where women represent half the population, it is difficult to understand how no woman can have the capacity to experience "the Lord's call."

Therefore, Jacqueline Straub has incisively knocked on the doors of the Vatican to obtain answers to what has so called her, but also to understand the resistance that keeps women away from the priesthood.

In letters sent to various Vatican officials, Jacqueline Straub has questioned why women's faith is not given equal value, and the responses she has received are troubling. While some responses are vague, many others are intended to intimidate her; they select passages from the Bible that violate the role of women and underline them in red.

For example, that passage where it says "Women must keep quiet," that letter signed by a certain Alexander was sent to Jacqueline's home, a fact that, at first, made her uncomfortable, but later, made her appropriate this emotion of fear and celebrate that, to a greater or lesser extent, her figure has become a thorn in the side of many men within the Vatican.

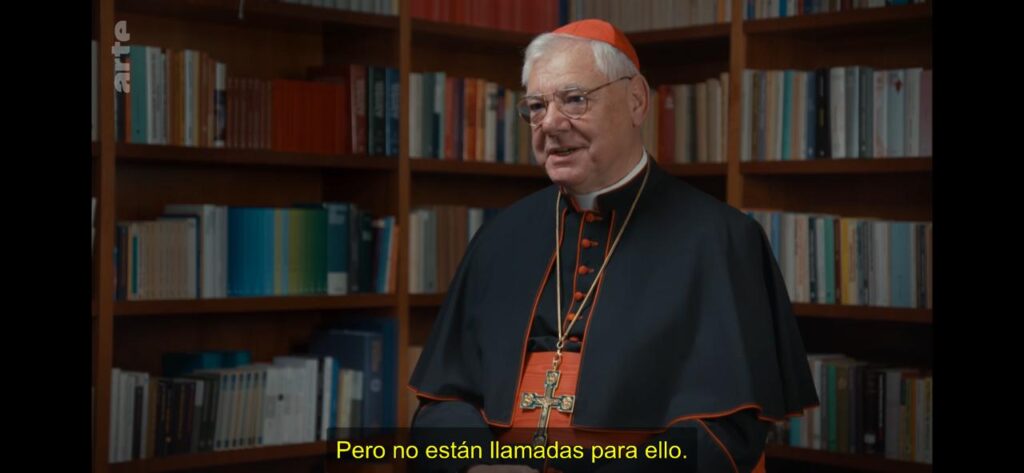

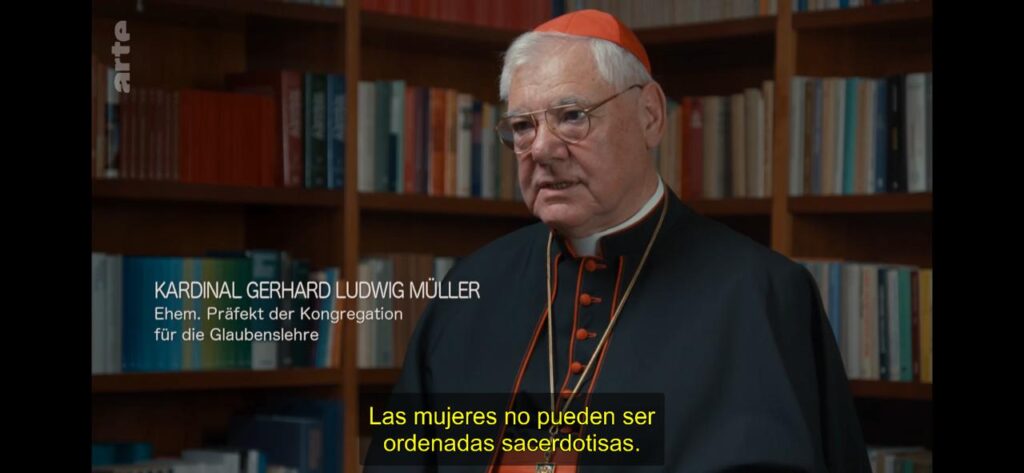

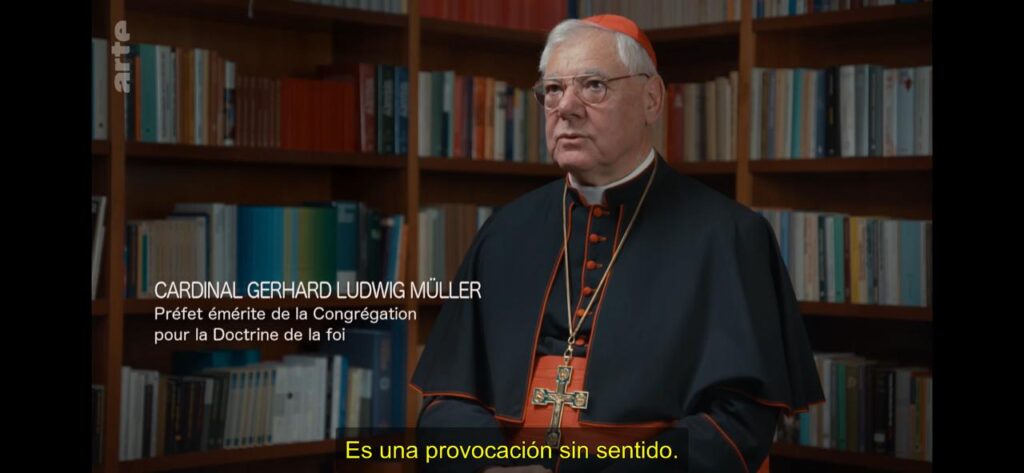

The episodes in the documentary where the journalist confronts various clerical authorities are difficult to watch. Particularly her confrontation with Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig, who categorically denies that Jacqueline felt "called by the Lord," as he would never do such a thing; he wouldn't be wrong to call a woman.

A moment of profound tension, where he directly denies the journalist's life experience, telling her that it's most likely all a mistake.

" It's a pointless provocation. Women cannot be ordained priests ," the cardinal responded to the journalist when she spoke to him about the figure of women as the Danube Seven. This response exposes the Church's devaluation of women who, against all odds, have been ordained priests and have dedicated— like any other man —their lives to studying and spreading the word of the Lord.

Although it may seem obvious, Jacqueline recalls something undeniable: the way the Church has "broken" the dreams of thousands of women. She ends her comment by saying she feels deeply hurt and sad, knowing that she will probably never become a priest.

During a public appearance with Pope Bergoglio, Jacqueline manages to approach him and tells him to please consider ordaining women and heed the call. However, the Pope simply says, "Be a good woman."

Breaking the Dream: Arrested, Punished, and Excommunicated

Christina Moreira "Luz Galilea" was another woman who was ordained, but she faced numerous setbacks in her quest to be recognized in the Church.

A survivor of domestic violence, Christina expresses the feeling of being called by the Lord, a mystical event that came to her as she meditated on the Gospel. She remembers looking at herself and asking the Lord why He had chosen her, and that it was probably a mistake.

Knowing the path wasn't easy, Christina chose to suppress her faith, as she would never succeed as a priestess. This fact broke her emotionally and psychologically, so much so that she even considered leaving the Church. She wanted to eliminate faith from her life rather than fight one of the most powerful bureaucratic monsters.

For security reasons, Christina changed her name to "Luz Galilea," and just a couple of years ago, while standing in Vatican Square, she was apprehended and questioned about why she was wearing priestly vestments, even though she had been ordained by another woman years earlier. Despite explaining her work and showing documentation, Christina was taken to the police station where she was questioned for two hours and later had her alb and stole confiscated.

But, where does this total rejection come from? Why can't the Church bear to see women as priestesses? There are two theories that support this segregation.

- God chose his 12 apostles as men

- Priests are an extension of Jesus, therefore, they must be in his likeness; a woman does not share the characteristics of the Lord.

However, feminist theology has vigorously debated these two facts, under the umbrella of hermeneutics—a reinterpretation of the Bible—which finds that, in fact, women always existed on Jesus' radar; Jesus called all people equally to replicate his teachings.

In addition, it has been shown that he also called women to follow him; powerful women who defended Jesus and were erased by the Church.

" The history of the Church is the history of the erasure of women for their own good and their worldview ," says theologian Jamie Mason.

Among the writings, one of the apostles named Junias has been found , but her name was changed to a masculine one. Likewise, it is known that Jesus named Mary Magdalene "The Apostle of the Apostles," a wealthy woman who gave her life to Jesus and who has been singled out by the Church as a prostitute, sinner, and adulteress, even though there is no record in the Holy Scriptures that explicitly states this, says Jamie Mason.

On a second note, do women really not look like Jesus? It's evident that not all men are like him either. Mason specifically points out that European or Asian men who also don't look like Christ have been ordained. Moreover, most of them are older men. Jesus was 33 years old, and that doesn't mean that Caucasian men in their old age have been prevented from ceasing their priesthood because they don't look like Jesus. And while this may seem ridiculous, it's the same logic that drives the segregation of women; it's archaic to expect one to look like Jesus in order to replicate his word.

Added to this is another, even more interesting layer that feminist theology has brought to the forefront: What if Jesus wasn't a man?

Feminist Theology: A Questioning of the World

In Mexico, liberation theology has been profoundly revelatory and is becoming a very strong part of religious reality, which means that it is not only gaining ground but is also fighting against the extraction of women's wisdom. And when we talk about theology, just as Vélez's work warned, ancestral and spiritual knowledge is also mentioned; this is not about some religious figure, but rather, a pure divinity that we attempt to reach from different fronts.

In an interview with Cimacnoticias , the theologian and current secretary of culture of Mexico City, Ana Francis Mor, explains that one of the things that feminist theology does is study, embrace and recognize all the spiritual knowledge of all traditions, so the conversation is extremely rich in terms of knowledge, from those who are dedicated to healing, to the earth, to the defense of the earth, to those who have been ordained as religious women 50 years ago and everything that has led them to think about their grassroots work.

This is precisely what feminist territory in religion is all about; the struggle to be and live faith from the feminine experience, a tool to which many women are attaching themselves, which is, in essence, a very important part: Diverse women are no longer excluded from the mandates of the Church, but rather free thinkers and builders of their own faith.

«We are women who do not want patriarchal submission, even those of us who are from a position as lesbians, that is to say, as if we have been expelled, you know? We are expelled from faith and spirituality, that led me to think: «Oh, gosh, why? I mean, thinking of faith also as the body, right? It is that territory to reclaim faith - faith, whatever that means for each of us -»

In addition to this same rebellion of women inserting themselves into the Church, another fundamental idea is born: Reappropriating the figure of God.

In a more focused conversation, Ana Francis Mor argues that when we talk about God—the word itself—it's not necessarily something that can be explained, not because it's nonexistent or magical, but rather because it's so vast. And it's this immensity that women are taking in hand to build their own refuges of faith; not the androcentric faith of "what should be" or what institutional frameworks dictate, but rather, from the very experience of living as women and, based on that, beginning to heal the violence to which we have been subjected.

«In many cultures it is the oneness of the whole and when I speak of the whole it is not that anything is God but the whole is like the conjunction of the whole, from all cultures practically all systems of religious knowledge tell you about a future in which everything dissolves into a single thing like a kind of Big Bang in reverse like a return to an energy where we are and where everything is together, -united, but not separated-.

So let's say in this tension, every system of sacred knowledge reflects this longing for it not to exist and this disunity or distance and in one way or another that is God (...) in most systems of sacred knowledge, even seriously in the study, no one suggests that it has even a form, a shape, or a sex, but that it is everything and thanks to patriarchy, we think that God is man" (Ana Francis Mor)

With this last reflection, we build the possibility of continuing to rethink (ourselves) and knowing that, out there, women are placed in every trench to continue breaking down the patriarchal system, some fighting in the streets and others, dynamiting the roots of the Church with the word "woman." No matter where the patriarchy hides, there are always fighters willing to write their own history.