October 19, 2025

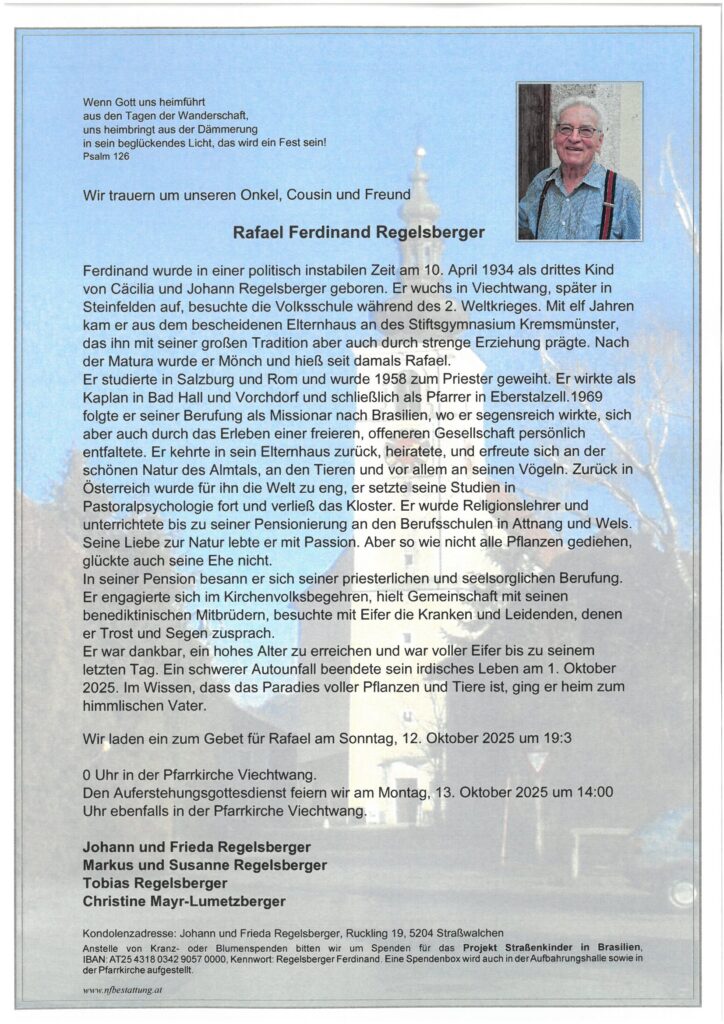

When women were ordained as Catholic priests for the first time on June 29, 2002—the Danube Seven —this required the disobedient actions of male bishops. One of them was Bishop Rafael Ferdinand Regelsberger. He died at the age of 91 after a traffic accident on October 1, 2025. With great humility, he was ordained a bishop to make the priesthood of women possible in the Catholic Church. For this, he accepted the penalty of excommunication.

THE SECRET CONSECRATION

The sun shone bright and warm from a cloudless blue sky as an unauthorized episcopal consecration took place in secret on May 9, 2002, in a town in Upper Austria. In a private chapel, the largely unknown, Spanish-speaking Bishop Antonio Braschi consecrated the former Benedictine Father Raphael from the nearby Kremsmünster Monastery, Ferdinand Regelsberger, who had been laicized since 1977, as bishop. The Vatican was informed, but ultimately powerless: That same night, the responsible Bishop of Linz, Maximilian Aichern, had notified the nunciature in Vienna.

The purpose of the secret episcopal ordination was to ensure the ordination of several women to Catholic priesthood, planned for June 29, 2002, at a location kept secret until the very last moment, by another willing bishop. And so it happened: Braschi and Regelsberger concelebrated the ordination of the seven women on the passenger ship MS Passau on the Danube. The third designated bishop, whose name remains unknown to this day, did not appear at the ordination. The purpose of the episcopal ordination deeply worried the Vatican; it attempted to learn more about the planned ordination of women in advance, especially the intended location, in order to be able to take action (legally?) against it if necessary. The successful secrecy surrounding the ordination preparations prevented this. Thus, the event became a press sensation.

The announcement of Regelsberger's episcopal ordination led to considerable unrest in the Diocese of Linz, which even reached the Vatican. The secular and ecclesiastical press had reported extensively on the matter—even before the consecration of the Danube Seven. Extensive speculation arose about the identity of the consecrating bishop, who was still unknown at the time. However, the mystery surrounding the location was revealed . Bishop Aichern of Linz publicly accused him of " schismatic " behavior. Regelsberger himself was not mentioned in the press, nor was his position on women's priesthood.

REGELSBERGER'S CAREER

Regelsberger was born on April 10, 1934, in Viechtwang, Upper Austria. At the age of 11, he attended the Stiftsgymnasium of the Benedictine monastery in Kremsmünster, where he earned his Matura (university entrance qualification). He then became a monk there, studied in Salzburg and Rome, and was ordained a priest in 1958. After several years in parish ministry, he followed his calling as a missionary to Brazil in 1969. He returned to Austria after three years, later left the order, and was laicized in 1977. After studying psychology, he married a former nun, but the marriage remained childless and lasted only 12 years.

In 1995, he became involved in the church referendumand thus joined the call for the introduction of the ordination of women. Until his retirement, he worked as a Catholic religion teacher at the vocational schools in Attnang and Wels. Interestingly, his active support of the ordination of women movement through his own ordination as a bishop, which was prohibited by canon law, and the ordination of the Danube Seven in 2002 is not mentioned in his otherwise detailed obituary.

EFFECTIVENESS OF EPISCOPAL ORDINATION

The identity of the ordainer is crucial for the effectiveness (validity) of a bishop's ordination. If the ordainer was indeed a bishop in the apostolic succession—and the Church apparently assumes this—then, in all likelihood, an illicit but valid episcopal ordination was performed on June 9, 2002 (valide, sed illicite).

As in the well-known case of Bishop Lefebvre (Sixth Pius Brotherhood), Canon 1382 of Canon Law would then apply. Accordingly, the Episcopal Ordinariate of the Diocese of Linz officially issued the following statement in the June 2002 Diocesan Bulletin under the heading "Excommunication": "According to Canon Law, both the bishop who ordains someone as bishop without papal mandate, as well as the person ordained by him, incur the automatic penalty of excommunication, the resolution of which is reserved to the Holy See. Canon Law prohibits any excommunicated person from performing any service at the Eucharist or at any other religious service, from administering or receiving sacraments (can. 1331 § 1 CIC). Therefore, priestly or episcopal functions by Mr. Regelsberger are not permitted."

“WHY I ORDAIN WOMEN”

Regelsberger's path to the Benedictine Order was paved by his attendance at the strict Benedictine abbey high school in predominantly Catholic Upper Austria. Thus, he was ordained a priest "despite all his doubts." He carried out the ministry with joy and success, as he himself put it, and with minor and major rebellions that were part of his life. This was followed by priestly burnout upon his return from the Brazilian mission, as well as dissatisfaction with authoritarian leadership structures in the order and the church. His psychology studies, which he had imposed against the order, combined with a midlife crisis, ultimately led to his leaving the order and a religious reorientation.

Regelsberger reports on this in his contribution to the book "We are Priestesses," published in 2002 by Patmos Verlag on the occasion of the consecration of the Danube Seven (ed. Werner Ertel and Gisela Forster). On July 26, 2002, the Archbishop's Ordinariate of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising obtained a preliminary injunction from the Munich I Regional Court against a passage in the book; it prohibited the claim that "at the end of June 2002, women were ordained as priests by Roman Catholic bishops." The remaining edition of the book was subsequently destroyed.

In the book, Regelsberger discusses his motives for disobedience: "It's a question of justice. The feminine side of God must also be made visible in women in the third millennium. It's sad that we are forced to act 'contra legem'; but the law of love obliges me to do so. For justice can only be established if this form of discrimination against women is ended in the Roman Catholic Church as well... He calls into his service whomever He wills."

OUTLOOK

Regelsberger's excommunication and the distancing of the order's superiors and many church representatives were painful for him. But the androcentric and misogynistic power of the church has long since been broken: Like many excommunicated people, Regelsberger was regularly given Holy Communion – contrary to the ban; four priests were present at his funeral on October 13, 2025. The distancing of the official church did not deter him from pursuing his calling as a pastor until the end and helping others. A priestess of the Danube Seven summarizes:

“Rafael was a wonderful person and one of our greatest supporters”

The participation of men—and thus their excommunication—is no longer required for the ordination of women. Twenty years after the ordination of the Danube Seven, women now confer priestly ordinations themselves, as they did during the World Synod in Rome . Approximately 20 female bishops are ready to ordain those women who feel called to the priesthood ( listed here by name as contact persons )—most recently the Spaniard Christina Moreira .

But men like Regelsberger are crucial for a discrimination-free future for the Church. Only when male priests and bishops also openly embrace the ordination of women and act contrary to canon law will there be a just Church. We know from church history that without such pressure, there can be no change in the Catholic Church. In this sense, Bishop Rafael Regelsberger was a courageous example. May he find many equally courageous successors.C

No comments:

Post a Comment